Home to the House of Wisdom (Bayt al-Hikma)

Introduction: Brief overview of the Siege of Baghdad

The Siege of Baghdad (1258) was one of the most catastrophic events in world history, marking the brutal end of the Abbasid Caliphate and a turning point in Islamic civilisation. Led by Hulagu Khan, grandson of Genghis Khan, the Mongols launched a devastating assault on Baghdad, the cultural and intellectual heart of the Islamic world. With an army estimated between 100,000 to 150,000 Mongols, reinforced by Christian allies and siege engineers from China and Persia, the Mongols besieged the city on 29 January 1258. Within just 12 days, the once-glorious capital of the Abbasids was reduced to smouldering ruins, with up to 200,000 to 1 million people massacred in one of the deadliest sackings in history.

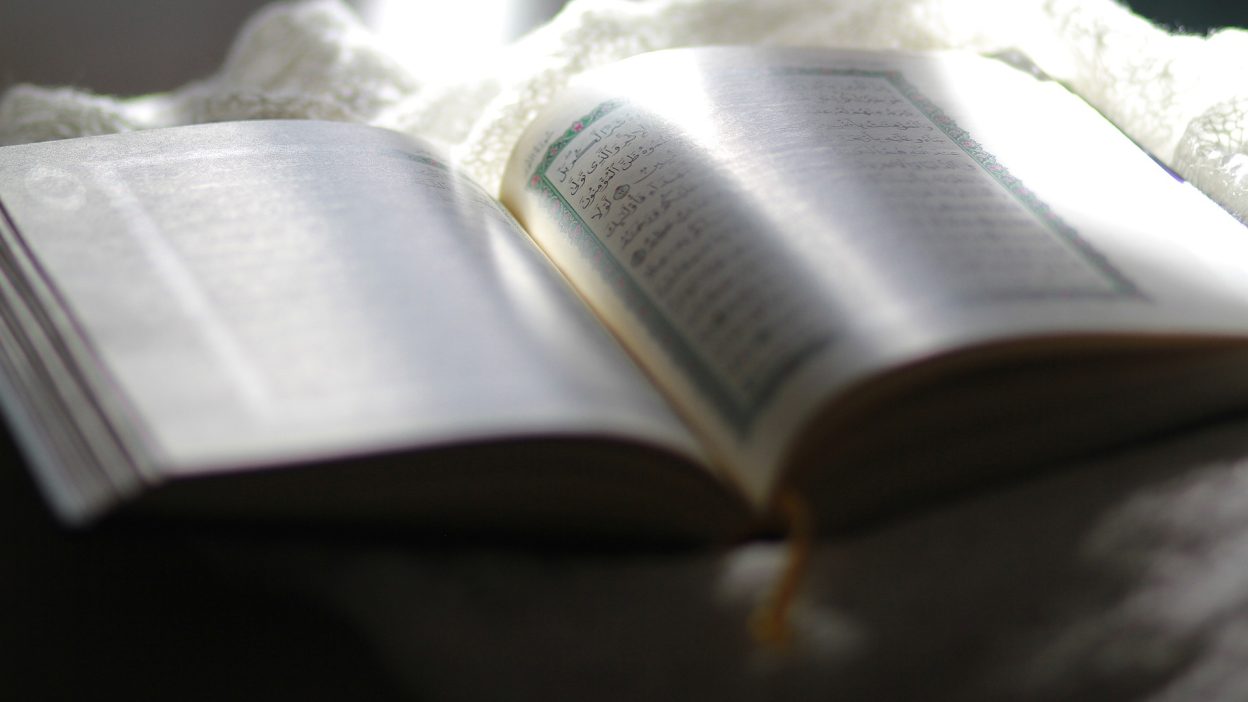

Baghdad was not just a political capital but the centre of Islamic learning, home to the House of Wisdom (Bayt al-Hikma), where scholars had preserved and expanded the knowledge of Greek, Persian, and Indian civilisations. This vast treasury of knowledge was destroyed, its books thrown into the Tigris River, allegedly turning the waters black with ink. The Mongols showed no mercy—even Caliph Al-Musta’sim, the last Abbasid ruler of Baghdad, was executed, reportedly wrapped in a carpet and trampled by horses to avoid spilling royal blood. The fall of Baghdad marked the symbolic and literal collapse of Islam’s Golden Age, leaving the Muslim world fractured and vulnerable.

The impact of this siege extended far beyond Baghdad. The once-mighty Abbasid Caliphate, which had ruled the Islamic world since 750 CE, was now shattered, its authority permanently diminished. The Mongols pushed further into Syria and Palestine, while the Islamic world struggled to recover from the devastation. Eventually, the Mamluks of Egypt emerged as the new defenders of Islam, halting Mongol expansion at the Battle of Ain Jalut (1260). However, the psychological and cultural scars of 1258 remain etched in history—a grim reminder of how a single event can bring an empire to its knees.

Background and Causes

The Abbasid Caliphate Before the Siege

Political and Military State of the Abbasids in the 13th Century

By the 13th century, the Abbasid Caliphate had become a shadow of its former self. Once a vast empire stretching from North Africa to Central Asia, the Abbasids had lost most of their territorial control, reduced to ruling only Baghdad and its surrounding regions. The real political and military power had shifted to regional dynasties such as the Ayyubids in Egypt and Syria, the Seljuks in Persia and Anatolia, and later the Khwarazmians. The caliphs, once supreme rulers of the Islamic world, had become symbolic religious figures with little authority outside their capital.

Militarily, the Abbasid army was weak and disorganised. The caliphs relied heavily on mercenaries, particularly Turkish, Kurdish, and Persian troops, who often lacked loyalty and discipline. Unlike the Mongols, who maintained a highly effective and mobile fighting force, the Abbasids had no standing army capable of defending Baghdad against a large-scale invasion. Their failure to maintain a strong military presence beyond Iraq made them vulnerable to external threats, particularly from the Mongols, who had already conquered much of Central Asia and Persia.

Decline of Abbasid Authority and Decentralisation

One of the key reasons for the Abbasid decline was political decentralisation. The caliphs had long lost their ability to control distant provinces, leading to the rise of independent and semi-independent states that no longer recognised Baghdad’s authority. The Seljuks, for example, had taken over much of Persia and Iraq by the 11th century, reducing the Abbasid caliphs to mere figureheads. Even after the Seljuks weakened, new power struggles emerged between different factions, including the Khwarazmian Empire, which briefly took control of Baghdad in 1238 before being crushed by the Mongols.

Moreover, internal conflicts within the Abbasid court further weakened their power. The later Abbasid caliphs, including Al-Musta’sim (r. 1242–1258), were seen as ineffective rulers more focused on courtly pleasures than governance. The empire’s administration suffered from corruption and inefficiency, with powerful viziers and court officials often manipulating the caliphs for their own gain. This political instability made it difficult for Baghdad to prepare for external threats, leaving it highly vulnerable when the Mongols arrived at its gates in 1258.

In summary, by the time Hulagu Khan launched his campaign, the Abbasid Caliphate was already in decline, politically fragmented, militarily weak, and incapable of defending itself. The siege and destruction of Baghdad were not just the result of Mongol aggression but also a consequence of centuries of internal decay and mismanagement.

The Mongol Invasion and March Towards Baghdad

Hulagu Khan’s Strategic Planning

In 1253, Möngke Khan, the Great Khan of the Mongols, ordered his brother Hulagu Khan to lead a massive military expedition into the Middle East. The primary objective was to expand Mongol rule, subjugate the remaining Islamic states, and eliminate threats to Mongol dominance. Hulagu’s orders specifically targeted three major powers: the Nizari Ismailis (Assassins) of Persia, the Abbasid Caliphate in Baghdad, and the Ayyubids in Syria. His campaign was meticulously planned, with a focus on overwhelming force, advanced siege warfare, and psychological intimidation. Hulagu amassed an army estimated between 100,000 and 150,000 soldiers, including Mongol cavalry, Chinese and Persian siege engineers, and auxiliaries from Christian and Muslim states. Unlike earlier Mongol raids, this campaign was not a simple plundering expedition but a calculated effort to permanently incorporate the region into the Mongol Empire.

As Hulagu advanced westward, he demonstrated his military prowess by first targeting the Nizari Ismailis, a secretive Shi’a sect based in the Alamut Castle of Persia. By 1256, he had systematically crushed their mountain fortresses, eliminating the Assassin strongholds that had long been a menace to rulers in the region. With Persia fully under Mongol control, Hulagu turned his attention to Baghdad, sending multiple warnings to Caliph Al-Musta’sim to surrender. However, the Abbasid ruler refused, underestimating the Mongol threat and failing to assemble an effective defence. Hulagu responded by marching towards Baghdad in late 1257, methodically destroying any opposition along the way.

The Role of Christian and Muslim Allies in the Mongol Army

Hulagu’s campaign was not fought by Mongols alone; he skillfully built alliances with Christian and Muslim forces who opposed the Abbasids. The Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia and the Principality of Antioch, both Christian states, actively supported the Mongols, providing soldiers, supplies, and strategic guidance. The Mongols had previously allied with Christian rulers in their wars against Muslim states, and this partnership continued during the siege of Baghdad. Georgian auxiliaries, who had suffered under previous Muslim invasions, also contributed troops to Hulagu’s forces.

Additionally, many local Muslim factions, particularly Persian and Turkish soldiers, served in Hulagu’s army. Some cities and commanders, fearing Mongol retaliation, surrendered rather than resist, allowing the Mongols to advance with minimal resistance. In contrast, those who resisted faced complete annihilation, reinforcing the Mongols’ reputation for merciless retribution. By the time Hulagu reached Baghdad in January 1258, his army was a well-organised and battle-hardened force, strengthened by advanced siege weapons such as Chinese trebuchets (catapults) and Persian engineers skilled in breaking city defences. With the Abbasids unprepared and isolated, Baghdad faced one of the most brutal assaults in history.

The Siege of Baghdad (29 January – 10 February 1258)

Mongol Army Size and Composition

The Mongol army that besieged Baghdad in 1258 was one of the most formidable forces assembled in medieval history. Estimates place the Mongol force between 100,000 and 150,000 soldiers, a massive number for the time. This force was not composed solely of Mongol warriors but also included Persian, Turkic, Georgian, Armenian, and Chinese troops, along with siege engineers recruited from China and Persia. Hulagu Khan, the Mongol commander, had spent years preparing for this campaign, ensuring that his army was equipped with the latest in siege warfare technology, including Chinese trebuchets (catapults), Persian mangonels, and gunpowder-based weapons.

One of the most significant factors in the Mongol army’s effectiveness was its superior organisation and discipline. The Mongols were expert horsemen, skilled in rapid movements, deception tactics, and encirclement strategies. They also had an efficient supply chain, ensuring their forces were well-fed and equipped throughout the campaign. The Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia and the Christian Principality of Antioch provided additional support, offering supplies and troops to assist in the siege. This diverse coalition of warriors made the Mongol army a highly adaptive and lethal force, capable of executing complex military operations with precision.

Abbasid Defences and Military Preparations

In contrast, the Abbasid Caliphate was woefully unprepared for an assault of this magnitude. Caliph Al-Musta’sim, the last ruler of Baghdad, failed to take the Mongol threat seriously and did not mobilise his forces adequately. The Abbasid army was far smaller than the Mongol force, with estimates ranging from 20,000 to 50,000 troops, many of whom were poorly trained mercenaries rather than professional soldiers. Baghdad’s defences relied mainly on its massive walls and moats, which had withstood previous invasions, but the city lacked the military strength to effectively counter a prolonged siege.

Additionally, Al-Musta’sim made critical diplomatic errors. Instead of attempting to secure alliances with powerful Muslim states like the Mamluks of Egypt or the Ayyubids of Syria, he relied on vague assurances from his advisors that the Mongols would not attack. Some sources suggest that his vizier, Ibn al-Alkami, secretly corresponded with the Mongols, possibly undermining the city’s defences. The Abbasids also failed to gather sufficient supplies within the city, leaving them vulnerable to starvation once the siege began.

Siege Tactics Used by the Mongols

The Mongols employed a combination of psychological warfare, advanced siege engines, and tactical deception to break Baghdad’s defences. As soon as they arrived, they encircled the city completely, cutting off all escape routes and supply lines. They then launched a relentless bombardment using powerful siege weapons, including Chinese catapults and Persian mangonels, which pounded the city walls day and night. Hulagu’s forces also diverted the Tigris River, causing flooding in some areas and weakening parts of Baghdad’s fortifications.

One of the Mongols’ most effective strategies was their systematic use of terror. They executed brutal massacres in nearby towns, spreading fear among Baghdad’s defenders. In some cases, they sent captured prisoners back into the city, mutilated and terrified, to demoralise the population. The Mongols also dug trenches and constructed mobile siege towers, allowing them to launch direct assaults on the city’s walls while avoiding return fire from defenders.

Weaknesses in the Abbasid Strategy

The Abbasid defence was marked by poor leadership, lack of coordination, and overreliance on static fortifications. Unlike the Mongols, who were experts in mobile warfare and siege tactics, the Abbasids had no experience defending against such a large-scale invasion. Their army was not properly trained for siege warfare, and they lacked the siege engines or cavalry forces needed to break the Mongol encirclement.

Furthermore, there was internal division within Baghdad. Many commanders distrusted Al-Musta’sim’s leadership, and some factions within the city reportedly refused to fight. Some sources claim that Ibn al-Alkami, the vizier, discouraged the caliph from organising a proper defence, possibly hoping to negotiate a surrender that would spare his own life. However, when the Mongols breached the city walls on 10 February 1258, no such mercy was granted—Baghdad fell in a matter of hours, leading to one of the most devastating massacres in history.

The combination of Mongol military superiority, Abbasid strategic failures, and internal betrayals ensured the fall of Baghdad. The siege ended not only the Abbasid Caliphate but also an era of Islamic dominance in science, culture, and politics. The destruction of Baghdad remains one of the most infamous events in world history, a tragic lesson in the consequences of political complacency and military unpreparedness.

The Fall of Baghdad (10 February 1258)

Breaking Through Baghdad’s Defences

After 12 days of relentless bombardment, the Mongols finally breached Baghdad’s defences on 10 February 1258. The city’s walls, weakened by continuous siege engine attacks and flooding caused by Mongol diversions of the Tigris River, could no longer withstand the pressure. Once the Mongols broke through, the Abbasid defenders—already outnumbered and demoralised—offered little resistance. The Mongols stormed into Baghdad, overwhelming the remaining Abbasid troops and massacring anyone who attempted to resist. Unlike previous invaders, who had often looted Baghdad but spared its core institutions, the Mongols were methodical in their destruction, aiming to completely eradicate Abbasid rule and make an example of the city.

One of the major reasons for the swift collapse of Baghdad’s defences was internal betrayal. Some historical sources suggest that Ibn al-Alkami, the Abbasid vizier, had secretly corresponded with the Mongols before the siege, encouraging them to invade. He allegedly convinced Caliph Al-Musta’sim not to mobilise the full strength of his army, claiming that resistance was futile and that the Mongols might spare the city if it surrendered. Whether or not this betrayal was deliberate, Al-Musta’sim’s indecisiveness and failure to organise a proper defence proved catastrophic. By the time the Mongols breached the city walls, there was no coordinated strategy to repel them, and Baghdad—one of the greatest cities of the medieval world—fell within hours.

Massacres and Destruction of the City

Once inside Baghdad, the Mongols unleashed a wave of destruction and slaughter unmatched in the city’s history. For a full seven days, Mongol forces methodically killed men, women, and children, showing no mercy to civilians, scholars, or religious leaders. Estimates of the death toll vary widely, with some sources claiming around 200,000 deaths, while others suggest numbers as high as 1 million. The streets of Baghdad were reportedly flooded with blood, and survivors recounted horrifying tales of Mongols piling bodies into pyramids as a display of power.

Perhaps the greatest tragedy of the sack was the destruction of the House of Wisdom (Bayt al-Hikma), the renowned library and intellectual centre of the Islamic world. This library, which housed thousands of manuscripts on science, mathematics, medicine, and philosophy, was burned and thrown into the Tigris River. According to legend, the river ran black with ink from the vast number of books destroyed. This event symbolised not just the fall of Baghdad but the end of an era of Islamic intellectual dominance, as centuries of accumulated knowledge were lost in a matter of days.

Religious sites were also targeted. The Mongols destroyed numerous mosques, madrasas (Islamic schools), and palaces, wiping out much of the city’s architectural and cultural heritage. The once-glorious Great Mosque of Baghdad, which had stood as a symbol of Abbasid power, was reduced to rubble. The devastation of Baghdad was so extreme that the city, which had once been the largest metropolis in the world, would never fully recover its former status.

The Fate of Caliph Al-Musta’sim and the Abbasid Royal Family

Caliph Al-Musta’sim, the last ruler of the Abbasid Caliphate in Baghdad, was captured along with his family and high-ranking officials. Hulagu Khan, despite showing leniency to some cities in the past, had no intention of sparing the caliph. Historians suggest that Hulagu initially mocked Al-Musta’sim, forcing him to witness the destruction of his city before deciding his fate. The Mongols, who followed a superstitious belief that royal blood should not be spilled on the ground, executed the caliph in a gruesome manner—he was wrapped in a carpet and trampled to death by Mongol horses.

The Abbasid royal family and members of the court suffered a similar fate. Some princes and nobles were executed, while others were taken as captives. The few survivors of the Abbasid dynasty fled to Egypt, where the Mamluk Sultanate later installed an Abbasid puppet caliph in Cairo to maintain symbolic religious legitimacy. However, the Abbasid Caliphate as a political power ceased to exist, and its fall marked the end of the Islamic Golden Age.

The fall of Baghdad in 1258 was not just a military defeat but a civilisational catastrophe. It shattered the Islamic world’s cultural and intellectual heart, eliminated the last remnants of centralised Abbasid rule, and left a power vacuum that would take centuries to fill. The Mongols moved on to conquer Syria and parts of the Levant, but their westward expansion was halted at the Battle of Ain Jalut (1260) by the Mamluks of Egypt. Nonetheless, the destruction of Baghdad remains one of the most infamous events in world history, a grim reminder of how even the greatest civilisations can fall due to military complacency, political mismanagement, and internal betrayal.

Aftermath and Consequences of the Siege of Baghdad (1258)

Immediate Aftermath

Death Toll and Devastation

The Mongol sack of Baghdad in February 1258 resulted in one of the worst massacres in history. The exact number of people killed remains uncertain, but historical estimates range between 200,000 and 1 million deaths. The Mongols, known for their brutal efficiency in warfare, carried out mass executions, killing men, women, children, and even religious scholars. The killing lasted for nearly a week, turning the once-thriving capital of the Islamic world into a wasteland of corpses and ruins. Eyewitness accounts describe how the Tigris River ran red with blood from the thousands slain and later turned black from the ink of books thrown into the river.

The Mongols did not just target people—they systematically destroyed Baghdad’s infrastructure. Palaces, mosques, schools, hospitals, and markets were looted and burned. The once-glorious city, which had served as the heart of the Islamic world for over 500 years, was left in ruins. Many buildings that had stood since the 8th and 9th centuries were completely erased from history. The destruction was so severe that Baghdad never fully recovered its former position as a leading centre of trade, culture, and governance.

The Destruction of the House of Wisdom and Loss of Knowledge

One of the most tragic consequences of the Mongol invasion was the destruction of the House of Wisdom (Bayt al-Hikma). This grand library and intellectual centre had been established by Caliph Harun al-Rashid and expanded by his son Al-Ma’mun. It housed thousands of books and manuscripts on subjects ranging from astronomy, mathematics, and medicine to philosophy and literature. Many of these texts were one-of-a-kind, containing centuries of accumulated knowledge from across the Islamic world, Persia, India, Greece, and China.

When the Mongols stormed Baghdad, they burned the House of Wisdom and threw its books into the Tigris River. According to historical reports, the ink from the destroyed manuscripts turned the river black for days, symbolising the intellectual and cultural catastrophe suffered by the Islamic world. The loss of this vast collection set back scientific progress in the Middle East, as many scholars who had depended on these resources were either killed or forced to flee. The destruction of Baghdad marked the end of the Islamic Golden Age, after which scientific and intellectual advancements in the region significantly declined.

The Fate of Baghdad’s Population and Survivors

In the aftermath of the siege, the surviving population of Baghdad faced horrific conditions. The Mongols continued their ruthless massacres, slaughtering anyone who had not already fled or hidden. Some reports indicate that even hospitals and mosques, which were traditionally spared in medieval warfare, were targeted. Survivors were left with no food or shelter, as the city’s grain stores and water supplies had been either destroyed or poisoned.

A small number of skilled workers—craftsmen, engineers, and scholars—were spared by the Mongols and taken to their empire to serve under Hulagu Khan. However, most of the elite class, including religious leaders, administrators, and military officials, were executed. The Mongols had no intention of restoring Abbasid rule and made it clear that Baghdad would no longer be a political or cultural powerhouse. Those who managed to escape fled to Egypt, Syria, or Persia, where they sought refuge under local rulers, particularly the Mamluks, who would later play a crucial role in stopping further Mongol expansion.

Impact on the Islamic World

The End of the Abbasid Caliphate as a Political Power

The fall of Baghdad in 1258 marked the definitive end of the Abbasid Caliphate as a political force. While the Abbasids had already lost most of their empire by the 10th and 11th centuries, they had remained a symbolic religious authority over the Islamic world. With Caliph Al-Musta’sim executed, the Mongols abolished the Abbasid line in Baghdad, leaving the Muslim world without a central caliphate for the first time since 632 CE.

Although a few Abbasid princes survived and later established a ceremonial Abbasid caliphate in Cairo under Mamluk protection, this was a symbolic institution with no real power. The fall of the Abbasids also meant that Baghdad was no longer the heart of Islamic civilisation. Other cities, such as Cairo, Damascus, and Samarkand, rose in prominence, but none matched the intellectual, cultural, and economic prestige that Baghdad had once held.

Shift of Islamic Leadership to the Mamluks in Egypt

With the Abbasids gone, leadership in the Islamic world shifted to the Mamluks of Egypt, who had been gaining strength in the previous decades. The Mamluk Sultanate, under the rule of Sultan Qutuz and later Baybars, took on the responsibility of defending the Muslim world from Mongol expansion. In 1260, just two years after the fall of Baghdad, the Mamluks dealt a decisive defeat to the Mongols at the Battle of Ain Jalut, halting their advance into the Middle East.

The Mamluks soon established a new Abbasid caliphate in Cairo, installing a surviving Abbasid prince as a puppet caliph. While this ensured the continuation of caliphal legitimacy, the real political power rested with the Mamluk sultans. For the next three centuries, the Mamluks would dominate the Islamic world, defending it from both Mongol and Crusader threats. However, the Islamic world would never again be united under a single powerful caliphate, as it had been under the Abbasids in their golden age.

Mongol Rule in Baghdad

Mongol Administration and Policies in Iraq

After the destruction of Baghdad, the Mongols incorporated Iraq into their empire, establishing the Ilkhanate, a Mongol state that ruled over Persia, Iraq, and parts of the Caucasus. Hulagu Khan appointed Mongol governors to oversee Baghdad, but the city was never fully rebuilt to its former glory. The Mongols ruled harshly, imposing heavy taxes on the surviving population and suppressing local revolts with extreme brutality.

Trade routes were disrupted, and many of Baghdad’s wealthy merchants and scholars had either been killed or fled. The city’s economy collapsed, and it took centuries for Baghdad to recover. Unlike their Chinese and Persian conquests, where Mongols eventually assimilated into local cultures, their rule over Baghdad was marked by destruction rather than integration.

The Ilkhanate’s Rule and Its Impact on the Region

Despite their initial brutality, the Mongols later adopted aspects of Persian and Islamic culture. By the late 13th century, many Ilkhanate rulers converted to Islam, beginning with Ghazan Khan in 1295. Under Mongol rule, Persian administrators and scholars played a role in stabilising the region, but Baghdad remained a shadow of its former self. The Ilkhanate eventually declined in the 14th century, giving way to new Islamic powers, including the Ottomans, Safavids, and Timurids, but the city never regained its golden age status.

The fall of Baghdad in 1258 remains one of the most devastating events in Islamic history. It marked the end of the Abbasid era, the destruction of a major centre of learning, and a power shift that permanently changed the political landscape of the Middle East. The Mongols, though eventually absorbed into local cultures, left a legacy of violence, destruction, and transformation, reshaping the Islamic world for centuries to come.

Legacy of the Siege of Baghdad (1258)

Impact on Islamic Culture, Science, and Governance

The fall of Baghdad in 1258 was not just the destruction of a city but the collapse of an intellectual and cultural empire that had flourished for centuries. Baghdad had been the heart of the Islamic Golden Age, a centre of science, philosophy, medicine, and literature. The destruction of the House of Wisdom (Bayt al-Hikma) and the loss of thousands of invaluable manuscripts set back scientific progress in the Islamic world for centuries. Scholars who had once gathered in Baghdad’s institutions were either killed, enslaved, or forced to flee to other regions, leading to a brain drain that severely weakened intellectual advancements in the Middle East. While cities like Cairo, Damascus, and Samarkand attempted to continue Baghdad’s legacy, none could fully restore the vibrant scholarly network that had once thrived under the Abbasids.

Politically, the siege marked the end of the Abbasid Caliphate as a central ruling power. Although a puppet Abbasid caliphate was later re-established in Cairo under Mamluk protection, it had no real authority beyond religious symbolism. The Islamic world fragmented into different regional powers, with the Mamluks in Egypt and Syria, the Ilkhanate Mongols in Persia and Iraq, and later the Ottomans, Safavids, and Timurids competing for dominance. This decentralisation led to internal conflicts that weakened the Muslim world, making it more vulnerable to later European expansion and colonisation.

Changes in Warfare and Mongol Strategies

The Mongol siege of Baghdad introduced and reinforced new military tactics and siege warfare techniques. Their use of Chinese, Persian, and Central Asian engineers to construct advanced siege engines, catapults, and trebuchets demonstrated the effectiveness of integrating knowledge from different cultures. The Mongols had already perfected the use of psychological warfare, using terror and mass executions to force cities into submission, and the fall of Baghdad reinforced their reputation for ruthless efficiency. Future Mongol campaigns in Syria, Anatolia, and Eastern Europe would follow similar patterns of devastation and strategic domination, though they were later halted by the Mamluks at Ain Jalut (1260) and by other resistance forces in different regions.

The destruction of Baghdad also changed the defensive strategies of Muslim and European powers. Realising the brutality of Mongol conquests, many cities in the Middle East and Europe invested in stronger fortifications, improved their diplomatic strategies, and sought alliances to counter Mongol threats. The Mamluks in Egypt, for example, strengthened their military, relying on highly trained slave soldiers (Mamluks) who would later defeat the Mongols and prevent further expansion into North Africa. The Mongols, despite their dominance, ultimately struggled to hold onto their conquests as their empire became too large and decentralised to effectively govern.

Modern Historical Interpretations

Historians today view the Siege of Baghdad as one of the most significant turning points in world history, marking the end of an era for the Islamic world and the beginning of new power dynamics in the Middle East. Some scholars argue that internal weaknesses, such as political corruption, military decline, and lack of unity, were as much to blame for Baghdad’s fall as the Mongol invasion itself. The incompetence of Caliph Al-Musta’sim and the possible betrayal by his vizier, Ibn al-Alkami, have been widely debated as contributing factors to the city’s downfall.

In a broader context, the destruction of Baghdad is often compared to other catastrophic events in history, such as the fall of Rome or the sacking of Constantinople, due to its long-lasting impact on civilisation. Some modern historians have also reassessed the Mongols beyond their brutality, noting that later Ilkhanate rulers, like Ghazan Khan, embraced Islam and contributed to rebuilding parts of the region. However, the sheer scale of destruction caused by Hulagu Khan’s forces in 1258 remains a defining moment in Islamic history, symbolising both the fragility of great empires and the long-lasting consequences of war.

Conclusion

The Siege of Baghdad in 1258 was more than just a military conquest; it was a catastrophic turning point that reshaped the Islamic world politically, intellectually, and culturally. The destruction of the Abbasid Caliphate, which had stood for over 500 years, left the Muslim world fragmented and leaderless, shifting power to regional dynasties like the Mamluks in Egypt and, later, the Ottomans in Anatolia. The Mongols’ brutal tactics and large-scale massacres resulted in one of the worst humanitarian disasters in history, with hundreds of thousands killed and the city reduced to ruins. The loss of the House of Wisdom, a global centre of knowledge, marked the end of the Islamic Golden Age, as centuries of scientific, philosophical, and literary advancements were burned, lost, or drowned in the Tigris River. Although Islamic scholarship survived in other regions, Baghdad never regained its former intellectual dominance.

The long-term consequences of the Mongol invasion extended far beyond Baghdad. The Mongols introduced new warfare strategies, permanently altering the military tactics of both Islamic and European powers. The fall of Baghdad also exposed the vulnerabilities of once-great empires, demonstrating that internal corruption, political disunity, and weak leadership could lead to complete destruction, regardless of past glory. While the Mongols eventually converted to Islam and contributed to regional governance, their initial conquest left scars that took centuries to heal. The siege stands as a reminder of the devastating impact of war on civilisation, showing how even the greatest cities can fall if they fail to adapt, unite, and defend themselves against external threats.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. Why did the Mongols attack Baghdad?

The Mongols attacked Baghdad as part of Hulagu Khan’s campaign to expand Mongol rule and punish the Abbasid Caliph Al-Musta’sim for refusing to submit to Mongol authority.

2. How long did the Siege of Baghdad last?

The siege lasted for 13 days, from 29 January to 10 February 1258, after which the Mongols stormed the city and carried out a week-long massacre.

3. What happened to Caliph Al-Musta’sim?

Caliph Al-Musta’sim was captured by the Mongols and executed, reportedly by being rolled in a carpet and trampled to death, to avoid spilling royal blood.

4. Did any Abbasids survive the Mongol invasion?

Yes, a few Abbasid family members escaped to Cairo, where the Mamluks later established a symbolic Abbasid Caliphate, though it had no real power.

5. How did the fall of Baghdad impact trade in the region?

Baghdad’s destruction disrupted trade routes, caused economic decline, and shifted commercial activity to other cities like Cairo and Damascus.

Reference:

Siege of Baghdad

Siege of Baghdad (1258)

Baghdad Sacked by the Mongols

Baghdad Sacked by the Mongols

The Sack Of Baghdad In 1258

How the Mongols Took Over Baghdad in 1258

YT links

How did the Mongols Destroy Baghdad in 1258

The end of the Islamic Golden Age: 1258 Historical Siege of Baghdad | Total War Battle

How the Mongols CONQUERED Baghdad, 1258 | Abbasid Apocalypse | Mongol Empire DOCUMENTARY