World War I’s Unforgiven Legacy: The Shattered Peace and Seeds of Future Conflict

The First World War, often called “The Great War,” marked a catastrophic chapter in human history. Spanning 28 July 1914 to 11 November 1918, it was a conflict of unprecedented scale that shattered the illusion of European invincibility. What began as a seemingly regional dispute in Sarajevo quickly spiralled into a global nightmare, pulling in over 30 nations and leading to the deaths of more than 16 million people, both soldiers and civilians. Touted as the “war to end all wars,” it instead laid the groundwork for the even more destructive conflict that followed two decades later. At the heart of the conflict were two powerful blocs: the Allied Powers, including Britain, France, Russia, and later the United States, and the Central Powers, dominated by Germany, Austria-Hungary, and the Ottoman Empire.

The trigger for this devastating war was the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria-Hungary on 28 June 1914, by Gavrilo Princip, a member of the Bosnian Serb nationalist group, the Black Hand. This act of political violence, carried out in Sarajevo, set off a chain reaction of military alliances and ultimatums. Austria-Hungary’s aggressive response to Serbia, backed by Germany, led to Russia mobilising in defence of its Slavic ally. Within weeks, Europe was plunged into war, with countries across the globe following suit. What had been an assassination in a small Balkan city became the first truly global war, stretching from the muddy trenches of France to the deserts of the Middle East.

This war introduced the world to modern industrialised combat, with machine guns, poison gas, and artillery killing on a scale never witnessed before. The introduction of tanks and the growing use of aircraft brought warfare to new dimensions, making it more impersonal, efficient, and horrific. The brutality of trench warfare defined the Western Front, where millions perished in futile attempts to gain mere metres of land. The human cost was staggering: nearly 10 million military deaths and over 6 million civilian deaths, with many more maimed, traumatised, or displaced. The war wasn’t just a battlefield event; it was a complete societal upheaval, leaving deep scars on families, economies, and nations.

But who was truly to blame? Many point to Germany‘s militaristic ambitions, bolstered by the Schlieffen Plan, which aimed to swiftly crush France before turning to Russia. Others blame the tangled web of alliances and a growing appetite for empire among European powers. Whatever the reasons, World War I destroyed the world order of the 19th century and reshaped the globe politically, socially, and economically. It gave rise to revolutions, toppled empires, and sowed the seeds for World War II, making it not just a war of trenches and treaties but a pivotal moment that redefined humanity’s trajectory.

Causes of World War I

The origins of World War I lie in a volatile mix of political ambition, national pride, and reckless alliances that turned Europe into a ticking time bomb. At the heart of the chaos was the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria-Hungary on 28 June 1914 in Sarajevo. The assassin, Gavrilo Princip, a 19-year-old Bosnian Serb and member of the nationalist group Black Hand, aimed to challenge Austria-Hungary’s grip on the Balkans. What should have been a regional dispute turned into a global catastrophe as Austria-Hungary, backed by Germany, issued an ultimatum to Serbia, leading to a chain reaction of military alliances. Russia mobilised to defend Serbia, prompting Germany to declare war on Russia, and soon, France and Britain were drawn in. Within weeks, Europe was engulfed in a war that would claim millions of lives.

Beyond the immediate spark of the assassination, the underlying causes of the war were deeply rooted in imperialism, militarism, nationalism, and the entangling system of alliances. The late 19th and early 20th centuries had seen European powers vie for global dominance, carving up colonies in Africa and Asia while building massive armies at home. Germany, unified in 1871, sought its “place in the sun,” challenging Britain’s naval supremacy and France’s colonial reach. The militarisation of Europe became a dangerous arms race, with nations stockpiling weapons and drafting war plans. Chief among these was Germany’s Schlieffen Plan, which aimed for a swift invasion of France through Belgium, violating neutrality and forcing Britain into the war. The arrogance of these plans underestimated the scale of the devastation they would unleash.

Perhaps the most explosive ingredient was nationalism. In the Balkans, ethnic groups sought independence from Austro-Hungarian rule, creating a hotspot of tension. Meanwhile, pan-Slavic ambitions backed by Russia clashed with Austrian and German interests. Nationalistic fervour wasn’t confined to the Balkans; across Europe, citizens were whipped into patriotic frenzies, believing in their nations’ inherent superiority. This toxic mix of pride, paranoia, and political miscalculation turned every diplomatic crisis into a potential spark for war. When the first shot was fired, it was not just an attack on Franz Ferdinand but on the fragile balance of power in Europe, transforming decades of rivalry into a conflict that would rewrite history.

Major Fronts and Theatres of War

World War I was a truly global conflict, fought across multiple theatres that showcased the brutality and devastation of modern warfare. The war’s scale stretched far beyond Europe, with fronts that epitomised humanity’s darkest moments and military ingenuity. Each front was marked by unique challenges, unimaginable suffering, and battles that altered the course of history. From the muddy trenches of France to the deserts of the Middle East, these theatres demonstrated the relentless reach of war.

The Western Front

The Western Front, stretching from the North Sea to the Swiss border, became infamous for its gruesome trench warfare. After Germany invaded Belgium in August 1914, violating its neutrality, the war quickly descended into a bloody stalemate. Soldiers lived in the squalor of trenches, enduring constant artillery fire, disease, and psychological torment. The horrors of No Man’s Land, a desolate expanse between opposing trenches littered with corpses, became a defining image of the war. The Battle of Verdun (21 February – 18 December 1916) was one of the longest and deadliest, with over 700,000 casualties, as Germany attempted to bleed France dry. Similarly, the Battle of the Somme (1 July – 18 November 1916) saw British and French forces suffer catastrophic losses, including 57,000 British casualties on the first day alone, in what became one of the bloodiest battles in human history.

The Eastern Front

While the Western Front was defined by static trench warfare, the Eastern Front was more fluid and expansive, covering the vast territories between Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Russia. Battles here were marked by massive movements of troops and devastating losses, with millions of soldiers and civilians killed or displaced. The Eastern Front saw the Russian Empire initially overwhelm Austria-Hungary, only to suffer disastrous defeats at the hands of Germany, particularly at the Battle of Tannenberg (26–30 August 1914), where the Russians lost 92,000 soldiers and faced one of the war’s most humiliating defeats. The vast distances and harsh conditions of the Eastern Front took a significant toll on troops, and by 1917, Russia’s political unrest led to the Bolshevik Revolution, effectively pulling it out of the war.

The Italian Front

Often overlooked in popular narratives, the Italian Front was a brutal yet lesser-known theatre of World War I. After Italy joined the Allies in 1915, it faced Austria-Hungary in a gruelling series of battles along the Isonzo River and in the harsh, mountainous terrain of the Alps. The region’s steep cliffs and freezing conditions added a new layer of suffering, as soldiers fought not only their enemies but also avalanches, frostbite, and high-altitude sickness. The Battle of Caporetto (24 October – 19 November 1917), in which Austro-Hungarian and German forces launched a crushing offensive, led to Italy’s humiliating retreat and the loss of 300,000 troops, leaving a deep scar on the nation’s psyche.

The Middle Eastern Theatre

The war also extended to the Middle East, where the crumbling Ottoman Empire, aligned with the Central Powers, became a key battleground. The Arab Revolt (1916–1918), led by figures such as T.E. Lawrence (popularly known as Lawrence of Arabia), sought to dismantle Ottoman control over the Arabian Peninsula. The desert campaigns were marked by guerrilla tactics, with Lawrence and Arab forces successfully sabotaging Ottoman supply lines and railways. Key victories, such as the capture of Aqaba (6 July 1917) and the advance on Damascus, symbolised the fall of the Ottoman Empire. The region’s strategic importance, particularly the control of oil and trade routes, ensured that the Middle Eastern theatre left a lasting geopolitical legacy that continues to shape the region today.

These fronts demonstrated the far-reaching devastation of World War I, each contributing to the immense death toll, widespread suffering, and the reshaping of global politics. Together, they serve as a grim reminder of the costs of unchecked militarism and the global consequences of regional conflicts.

Technology and Weaponry in World War I

World War I was a watershed moment in the history of warfare, marking the dawn of modern, industrialised combat. For the first time, human ingenuity was harnessed on a massive scale to design weapons that could kill efficiently, devastating soldiers and civilians alike. From machine guns to poison gas, the war was a grim showcase of humanity’s capacity for destruction. The battlefield was transformed into a deadly laboratory, where innovation and death went hand in hand. Nowhere was this more evident than in the introduction of the tank in 1916, a revolutionary weapon first deployed by the British Army during the Battle of the Somme. These armoured vehicles were slow and cumbersome at first, but they were designed to break the deadlock of trench warfare by crushing barbed wire and crossing enemy trenches. Although their early use was limited, tanks signalled a shift towards mechanised warfare that would dominate the 20th century.

The machine gun became the most iconic weapon of the conflict, transforming battlefields into slaughterhouses. Capable of firing 500-600 rounds per minute, weapons like the Maxim gun and Germany’s MG 08 rendered traditional infantry charges suicidal. The impact was devastating during battles such as the First Battle of the Marne (6–12 September 1914) and Verdun (1916), where soldiers were mown down in their thousands. The widespread use of artillery magnified the carnage, with massive bombardments that obliterated trenches, tore apart human bodies, and reshaped landscapes. Shellfire caused the majority of deaths and injuries during the war, leaving survivors traumatised, shell-shocked, and disfigured. Adding to the terror, poison gas was introduced, first by the Germans at the Second Battle of Ypres on 22 April 1915. Chlorine gas and, later, phosgene and mustard gas caused agonising deaths, blinding, and long-term suffering. Gas masks became a grim necessity on all sides, but no technology could fully erase the fear of these invisible killers.

Beyond the land, the war reached the skies and seas with groundbreaking technologies. Aircraft—once limited to reconnaissance—quickly evolved into tools of combat. By 1915, fighter planes, such as the German Fokker Eindecker, introduced mounted machine guns that could fire through propellers, turning aerial dogfights into deadly spectacles. Strategic bombings by zeppelin airships targeted civilian populations for the first time, blurring the line between combatants and non-combatants. At sea, the war was dominated by Germany’s U-boat campaign, which utilised submarines to wage unrestricted warfare against Allied shipping. The sinking of the RMS Lusitania on 7 May 1915, which claimed 1,198 lives, including 128 Americans, escalated tensions and contributed to the United States entering the war in 1917. Naval innovations, such as the use of depth charges and convoys, were developed to counter the deadly efficiency of the U-boats.

The unprecedented scale and lethality of these technologies not only defined World War I but also set the stage for future conflicts. By mechanising death and destruction, the war stripped combat of its remaining vestiges of honour and chivalry. The weapons of World War I did not just kill soldiers—they shattered nations, destroyed landscapes, and created a legacy of fear and innovation that continues to shape warfare to this day.

The Home Front and Civilian Impact

World War I was not just fought on the battlefields—it infiltrated every aspect of civilian life, reshaping societies and forcing millions to endure hardships and sacrifices on an unimaginable scale. Across Europe and beyond, governments mobilised their populations like never before, transforming entire nations into war machines. Civilians became participants in a war that spared no one. Rationing, propaganda campaigns, and the pressure to purchase war bonds became daily realities, as governments scrambled to fund their militaries and sustain morale. Food shortages, caused by naval blockades and disrupted supply chains, hit countries like Britain and Germany particularly hard. In Britain, the introduction of rationing in 1918 aimed to ensure fair distribution of essential items like meat, sugar, and butter, but long queues and empty shelves highlighted the war’s toll on ordinary citizens. Germany’s Turnip Winter of 1916–1917 was even more dire, with millions forced to survive on animal fodder as starvation loomed.

Propaganda became a powerful weapon on the home front, designed to rally support, demonise the enemy, and inspire enlistment. Posters plastered cities, urging men to fight for their nations and shaming those who didn’t. In Britain, the famous image of Lord Kitchener, with the slogan “Your Country Needs YOU,” became a symbol of patriotic duty. Women were encouraged to send their husbands and sons to war, while films, newspapers, and public speeches were saturated with messages of national pride. The sale of war bonds became a patriotic duty, with governments urging citizens to invest in the war effort. These financial instruments not only funded military operations but also created a sense of shared sacrifice. However, the pressure to contribute financially and emotionally strained countless families, leaving deep scars long after the war ended.

Perhaps the most profound shift on the home front was the changing role of women. As men left for the trenches, women stepped into roles that had traditionally been denied to them. In Britain, over 800,000 women worked in munitions factories, enduring dangerous conditions to produce the weapons needed for the front. Many also served as nurses on the front lines, with organisations like the Voluntary Aid Detachments (VADs) providing critical care to wounded soldiers. The bravery and resilience of women during the war led to significant social changes, paving the way for movements advocating suffrage and gender equality. Yet, the end of the war often forced women back into traditional roles, highlighting the temporary nature of their wartime independence.

Civilian casualties were another grim reality of the war. The German Zeppelin raids on British cities like London and Scarborough, beginning in 1915, introduced the terrifying concept of aerial bombings, killing over 1,500 civilians and wounding many more. Starvation, disease, and displacement ravaged populations in war-torn regions, with millions of civilians in Belgium, Serbia, and Poland bearing the brunt of the conflict. The war left deep psychological scars, as families mourned the loss of loved ones and entire communities were left to rebuild shattered lives. On the home front, World War I was not just a story of resilience—it was a grim testament to the far-reaching consequences of total war.

Turning Points in the War

The entry of the United States into World War I in 1917 marked a pivotal turning point that shifted the balance of power decisively in favour of the Allies. While America had initially maintained a position of neutrality under President Woodrow Wilson, events such as the sinking of the RMS Lusitania on 7 May 1915 by a German U-boat began to erode public sentiment. The attack, which claimed the lives of 1,198 people, including 128 Americans, sparked outrage across the United States and heightened tensions with Germany. However, it was the revelation of the Zimmermann Telegram in January 1917—a secret German proposal encouraging Mexico to join the war against the U.S.—that ultimately tipped the scales. In April 1917, Wilson delivered his historic speech to Congress, declaring war on Germany to “make the world safe for democracy.” The influx of two million American troops and vast industrial resources breathed new life into the exhausted Allied forces, hastening the defeat of the Central Powers.

Another defining moment was the Russian Revolution of 1917, which transformed the Eastern Front and reshaped the war’s trajectory. Years of heavy casualties, poor leadership under Tsar Nicholas II, and severe economic hardship fuelled discontent across Russia. In March 1917, the tsar abdicated, and a provisional government was established. However, continued participation in the war exacerbated unrest, culminating in the Bolshevik Revolution in November 1917, led by Vladimir Lenin. The Bolsheviks immediately sought peace with the Central Powers, signing the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk on 3 March 1918, which ceded vast territories to Germany, including Ukraine, Poland, and the Baltic States. While this withdrawal allowed Germany to focus its efforts on the Western Front, it also contributed to the eventual collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and fuelled revolutionary movements worldwide. The Russian Revolution not only removed a key player from the war but also heralded a new era of global political change.

Provocative Battles That Changed History

The Gallipoli Campaign (1915–1916): Churchill’s Greatest Failure

The Gallipoli Campaign remains one of the most catastrophic Allied military failures of World War I, cementing its place as a haunting chapter in British history. Initiated in April 1915, the campaign was a bold but disastrously executed attempt to seize the Dardanelles Strait, a strategic waterway controlled by the Ottoman Empire. The brainchild of Winston Churchill, then First Lord of the Admiralty, this operation sought to open a supply route to Russia and knock the Ottoman Empire out of the war. However, it quickly devolved into a nightmare. Poor planning, lack of reconnaissance, and fierce resistance from the Ottomans, led by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, turned the operation into a bloodbath. The Allied forces, comprising British, Australian, New Zealand, and French troops, faced brutal conditions—searing heat, disease, and relentless enemy fire. The campaign dragged on until January 1916, ending in humiliating withdrawal and the loss of over 250,000 Allied troops, making it one of Churchill’s most controversial failures.

The Battle of Jutland (31 May – 1 June 1916): The Largest Naval Clash

The Battle of Jutland, fought off the coast of Denmark, was the largest naval battle of World War I and the only major fleet action of the conflict. Taking place between 31 May and 1 June 1916, it pitted the British Royal Navy’s Grand Fleet, under Admiral John Jellicoe, against the German High Seas Fleet, commanded by Vice Admiral Reinhard Scheer. The stakes were immense—control of the North Sea and the vital shipping lanes critical to Britain’s survival. The battle saw a staggering 250 ships engage in fierce combat, resulting in the loss of 14 British ships and 11 German ships, with nearly 10,000 sailors killed. Although the Germans claimed a tactical victory due to fewer losses, the British retained strategic control of the seas, effectively continuing the blockade that crippled Germany’s economy. The battle’s inconclusive outcome sparked controversy, with critics questioning Jellicoe’s cautious tactics and missed opportunities to decisively crush the German fleet.

The Spring Offensive (1918): Germany’s Last Gamble

The Spring Offensive, launched by Germany in March 1918, was their desperate final attempt to break the stalemate on the Western Front before American forces could fully tip the scales in favour of the Allies. Devised by General Erich Ludendorff, the offensive—also known as the Kaiserschlacht (Kaiser’s Battle)—was a series of blistering assaults targeting British and French forces. The Germans deployed new tactics, including stormtroopers, specially trained units that bypassed enemy strongholds to strike deep behind Allied lines. The offensive achieved initial success, advancing 65 kilometres and creating the deepest breakthroughs seen since 1914. However, the gains came at an enormous cost. German forces were overstretched, supply lines faltered, and morale collapsed as reinforcements failed to materialise. By July 1918, the Allies, bolstered by American troops and coordinated counterattacks, turned the tide at battles like the Second Battle of the Marne. The Spring Offensive, which had cost over 688,000 German casualties, proved to be Germany’s final gamble, ultimately leading to their collapse and the signing of the Armistice on 11 November 1918.

The Armistice and the End of the War

On the 11th hour of the 11th day of the 11th month in 1918, the guns fell silent across the Western Front, bringing an end to one of the most devastating conflicts in human history. The Armistice of Compiègne, signed in a railway carriage in the forest of Compiègne, France, marked the cessation of hostilities between the Allied Powers and Germany. This moment was the culmination of four years of relentless fighting that had left Europe in ruins. The decision to agree to an armistice was driven by Germany’s crumbling war effort—crippled by the Allied Hundred Days Offensive, internal political unrest, and the exhaustion of both military and civilian resources. German officials, led by Matthias Erzberger, signed the agreement with Allied representatives, including French Marshal Ferdinand Foch, who was determined to secure an unconditional end to Germany’s aggression. Though the armistice ended active fighting, the political and economic turmoil it created set the stage for further global conflict.

The human cost of World War I was staggering. By its conclusion, the war had claimed the lives of over 16 million people, including 10 million soldiers and 6 million civilians, with an additional 20 million wounded. Countries like France, Germany, and Russia were left scarred by the loss of an entire generation. The Western Front had witnessed unparalleled destruction, with battles like Verdun and the Somme resulting in horrific casualties. In France, entire villages were obliterated, while cities like Ypres became symbols of devastation. For the survivors, the end of the war did not bring immediate relief—economic instability, food shortages, and the Spanish flu pandemic wreaked havoc on already weakened nations. The Armistice of 1918, though celebrated, marked the beginning of a long and tumultuous journey toward rebuilding a shattered world.

The Treaty of Versailles (28 June 1919): A Controversial End to War

The Treaty of Versailles, signed on 28 June 1919 at the opulent Palace of Versailles near Paris, was the formal agreement that officially ended World War I. However, rather than establishing lasting peace, it planted the seeds of resentment and conflict. The treaty imposed harsh terms on Germany, forcing the defeated nation to accept full responsibility for the war through the infamous Article 231, also known as the “War Guilt Clause.” This clause laid the foundation for staggering reparations, amounting to 132 billion gold marks (approximately £6.6 billion) in 1921, crippling Germany’s already devastated economy. Additionally, Germany was stripped of 13% of its territory and 10% of its population, with regions like Alsace-Lorraine returned to France, the Saar Basin placed under League of Nations administration, and Eastern Prussia ceded to the newly independent Poland. The loss of overseas colonies, coupled with severe military restrictions, including a limitation of the German army to 100,000 troops and a ban on tanks, aircraft, and submarines, humiliated the nation and provoked widespread outrage.

The Treaty of Versailles also redrew the map of Europe, leading to the creation of new nations and unresolved tensions. The collapse of empires—Austria-Hungary, Ottoman, and Russian—gave rise to states such as Czechoslovakia, Yugoslavia, and Estonia, while borders were redrawn in ways that left many ethnic groups displaced or marginalised. In the Middle East, the treaty’s provisions handed control of former Ottoman territories, such as Iraq and Palestine, to Britain and France under mandates, sowing future discord in the region. The treaty also birthed the League of Nations, an international organisation meant to prevent future wars, but its lack of enforcement power and the absence of major players like the United States undermined its effectiveness. The Treaty of Versailles, though heralded as a solution to war, left Germany embittered and economically ravaged, laying the groundwork for the rise of Adolf Hitler and the outbreak of World War II just two decades later.

The Consequences of World War I: A Devastation That Reshaped the World

World War I ended in 1918, but its consequences reverberated far beyond the battlefield, shaking the foundations of global politics, economies, and societies. The war destroyed empires, collapsed economies, and sowed the seeds for an even greater catastrophe. The empires of Austria-Hungary, Germany, Russia, and the Ottoman Empire, which had dominated vast regions for centuries, crumbled under the weight of military defeat, revolution, and internal decay. In 1919, the map of Europe was redrawn, and the power dynamics shifted. Former empires gave way to fragile nation-states like Czechoslovakia, Yugoslavia, and Poland, while the rise of nationalist movements in colonies began to weaken imperial control globally. The end of these empires marked not just the collapse of old powers but the start of political instability that would define much of the 20th century.

Economically, the aftermath of World War I plunged Europe into financial ruin, paving the way for the Great Depression. The Treaty of Versailles imposed crushing reparations on Germany, amounting to 132 billion gold marks in 1921, which decimated the nation’s economy and left millions destitute. Hyperinflation gripped Germany in the early 1920s, reducing its currency to worthless paper and forcing citizens to carry money in wheelbarrows to buy bread. Across Europe, the cost of rebuilding was staggering, as war-torn nations struggled to recover from destroyed infrastructure, lost labour forces, and disrupted economies. The United States, which emerged as a creditor to many European nations during the war, became a major global financial power, but the 1929 stock market crash further exacerbated the financial strain. The war did not just bankrupt countries; it left societies fractured, with widespread poverty, unemployment, and political unrest becoming the norm.

The end of World War I did not bring peace; it brought resentment and the rise of ideologies that would lead to World War II. The harsh terms of the Treaty of Versailles deeply humiliated Germany, creating fertile ground for extremist ideologies. By forcing Germany to accept blame for the war through the War Guilt Clause (Article 231), the treaty ignited a burning anger among its population. The collapse of the German monarchy in 1918, followed by years of economic despair and political instability, allowed Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party to exploit national grievances. By 1933, Hitler had risen to power, promising to restore Germany’s pride and reverse the humiliation of Versailles. The war also fuelled the rise of fascism in Italy, where Benito Mussolini capitalised on post-war disillusionment to seize control in 1922. These movements were not just political reactions but direct consequences of the unresolved tensions and economic fallout of the Great War.

The Ottoman Empire’s dissolution after the war also led to profound geopolitical changes, particularly in the Middle East. The empire’s former territories were divided between Britain and France under League of Nations mandates, giving rise to modern nations like Iraq, Syria, and Palestine. This redrawing of borders, often done with little regard for ethnic or religious groups, set the stage for decades of conflict in the region. Meanwhile, in Russia, the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917, driven in part by the war’s devastation, established the world’s first communist state under Vladimir Lenin, creating a new ideological battleground that would dominate global politics for the next century. The consequences of World War I were not just immediate; they were generational, transforming the world into a landscape of political extremism, economic instability, and unresolved conflicts that continue to shape history.

Propaganda and Media During the War: Manipulating Minds and Shaping History

World War I saw the unprecedented use of propaganda to mobilise public opinion, maintain morale, and demonise the enemy. Governments across Europe unleashed a tidal wave of carefully crafted posters, films, and newspaper articles to shape the perception of the war. In Britain, posters like the iconic “Your Country Needs YOU”, featuring Lord Kitchener, were designed to guilt men into enlisting. Newspapers, heavily censored by governments, reported sanitised accounts of battles, focusing on heroism while minimising losses. The goal was clear: to sustain public support for a war that, by 1916, had already claimed millions of lives. Meanwhile, in Germany, propaganda portrayed the Allies as brutal aggressors, rallying citizens to defend the Fatherland. Films, a relatively new medium, were utilised to both inspire patriotism and spread misinformation. The power of media was not limited to print and film; even children’s books and songs were rewritten to glorify the war effort, embedding pro-war sentiment into society at every level. Propaganda blurred the line between truth and manipulation, creating a war fought not just on the battlefield but in the minds of millions.

War correspondents also played a critical role in controlling the narrative of the conflict. While the frontlines were scenes of unimaginable carnage, reports from journalists often omitted the full horrors. Correspondents like Philip Gibbs, writing for British newspapers, were bound by government censorship and could only publish stories that adhered to the desired narrative. Stories of bravery and camaraderie were highlighted, while the grim realities of trench warfare, such as rampant disease and mass death, were downplayed. In some cases, journalists were embedded with troops, but their reporting was closely monitored, ensuring it aligned with the propaganda machine. However, the media’s sanitised portrayal of the war began to unravel by 1917, as returning soldiers and rising casualty lists made the true cost of the conflict impossible to ignore. Propaganda and media, while instrumental in shaping public opinion, left a legacy of mistrust, as citizens began to question how much of what they had been told was truth and how much was carefully curated deception. The war’s media campaigns proved the terrifying power of information in shaping both a nation’s will to fight and its perception of reality.

Unsung Heroes of World War I: Forgotten Sacrifices in the Shadows of History

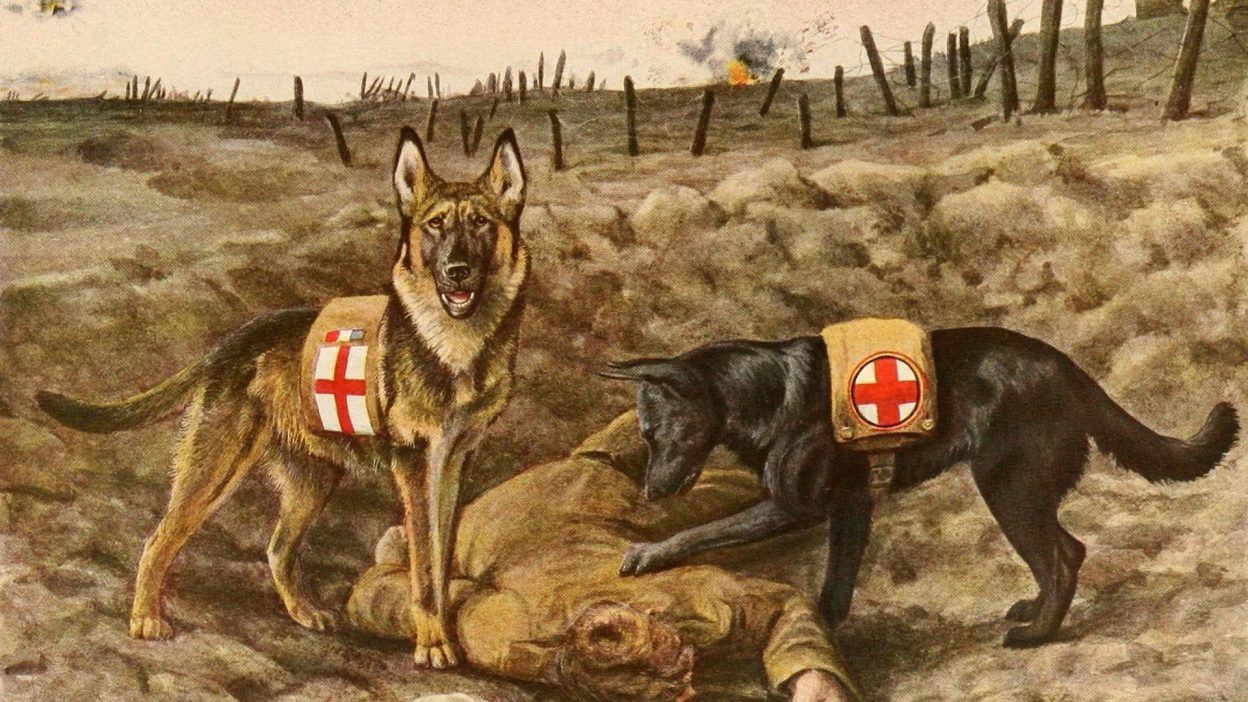

World War I is often remembered for its epic battles, political alliances, and staggering loss of life, but the contributions of countless unsung heroes remain largely overlooked. Among these were the colonial troops, whose sacrifices and efforts were critical to the Allied war effort. Over 1.3 million Indian soldiers, under British command, fought on fronts ranging from France to Mesopotamia (modern-day Iraq). Despite their pivotal role in battles such as Neuve Chapelle in 1915, where over 4,700 Indian soldiers lost their lives, they were rarely recognised or celebrated. Similarly, soldiers from Africa, particularly the Senegalese Tirailleurs, fought valiantly for France, enduring brutal conditions on the Western Front. By the war’s end, over 200,000 African soldiers had served, with 30,000 killed in action, their contributions often overshadowed by racial prejudice and exploitation. Troops from the Caribbean, including the British West Indies Regiment, faced similar discrimination, performing arduous labour behind the lines, yet still contributing to the war’s logistics and infrastructure. These soldiers fought for empires that viewed them as second-class citizens, and their heroism remains an overlooked chapter in the history of the Great War.

The sacrifice of nurses and medics during the war is another story of heroism overshadowed by the narratives of generals and politicians. Women like Edith Cavell, a British nurse working in German-occupied Belgium, risked everything to treat wounded soldiers from both sides of the conflict. Cavell’s humanitarian efforts saved countless lives, but her execution by a German firing squad on 12 October 1915, for allegedly aiding Allied soldiers’ escape, shocked the world. Her death became a powerful symbol of wartime injustice, but it also highlighted the dangerous conditions faced by medical personnel. Thousands of nurses, including Vera Brittain, author of Testament of Youth, endured relentless bombings, exhaustion, and emotional trauma in makeshift hospitals close to the frontlines. These women, often working without adequate resources, managed to treat injuries that included everything from shrapnel wounds to the effects of chemical warfare. Their efforts not only saved lives but also set a precedent for women’s expanded roles in society, although their contributions were seldom acknowledged in the immediate post-war years.

The unsung heroes of World War I faced adversity not only from the enemy but from the very systems they served. Colonial troops returned home to societies that denied them equality, their sacrifices unrecognised by the empires they fought for. Nurses and medics, hailed as angels of mercy during the war, were often pushed back into traditional roles once the conflict ended, their stories fading from public memory. The contributions of these individuals—Indian sepoys, African riflemen, Caribbean labourers, and tireless medical workers—underscore the war’s global scope and the countless lives touched by its horrors. Yet, their legacies are not merely about sacrifice; they are a testament to resilience, courage, and the fight for dignity in the face of unimaginable hardship. The Great War may have ended in 1918, but the struggle for recognition of these forgotten heroes continues to this day.

Culprits and Controversies: The Blame Game of World War I

The origins of World War I remain one of the most debated topics in history, with blame being cast across nations and leaders. At the heart of this controversy lies the role of Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Serbia. On 28 June 1914, the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo by Gavrilo Princip, a member of the Serbian nationalist group Black Hand, ignited the flames of war. Austria-Hungary’s swift retaliation in the form of an ultimatum to Serbia is often seen as the first step toward conflict. However, it was Germany’s infamous “blank cheque” of unconditional support to Austria-Hungary that escalated the crisis. Germany’s leadership under Kaiser Wilhelm II believed a swift, decisive war could bolster its dominance in Europe. Critics argue that Germany’s militaristic ambitions and its initiation of the Schlieffen Plan, which violated Belgium’s neutrality, transformed what could have been a regional conflict into a global catastrophe. On the other hand, Serbia’s support for nationalist movements in the Balkans, coupled with Austria-Hungary’s desire to crush Serbian ambitions, makes them equally culpable in lighting the fuse.

The assassination itself raises profound questions about Gavrilo Princip’s role in history. Was he a nationalist hero fighting against Austrian oppression, or a terrorist who plunged Europe into chaos? Princip, just 19 years old, fired the fatal shots that killed Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife, Sophie, on the streets of Sarajevo. For Serbian nationalists, he was a martyr who sought to free Bosnia and Herzegovina from Austrian control. However, for Austria-Hungary and its allies, Princip was nothing more than a terrorist, a pawn in Serbia’s reckless game of provoking war. His actions, driven by ideals of Slavic unity, unintentionally set in motion a chain of events that led to the deaths of over 16 million people. Even today, his legacy is deeply polarising—celebrated by some as a freedom fighter, condemned by others as a symbol of extremism. This dichotomy reflects the deep divisions over the interpretation of responsibility for the war’s outbreak.

Adding to the controversy were the catastrophic failures of Allied leadership during the war, which led to the unnecessary deaths of millions. Military strategies, especially on the Western Front, were marked by a horrific disregard for human life. Figures like General Douglas Haig, leading the British forces, have been criticised for their tactics during the Battle of the Somme in 1916, where over 57,000 British soldiers became casualties on the very first day. Despite repeated failures, Allied commanders persisted with frontal assaults on heavily fortified German positions, resulting in staggering losses. Similarly, the Gallipoli Campaign of 1915, masterminded by Winston Churchill, turned into a disaster for the Allies, with over 250,000 casualties and no tangible strategic gains. These decisions reveal the cold, brutal calculus of war, where human lives became expendable in pursuit of victory. The blame for World War I, therefore, does not rest solely on the shoulders of the nations involved at its outset but extends to the architects of its execution, whose failures magnified the suffering on an unimaginable scale.

Life in the Trenches: A Living Hell Beneath the Battlefield

Life in the trenches during World War I was a gruelling and dehumanising ordeal that stripped soldiers of their dignity, health, and humanity. Trench warfare, which dominated the Western Front from 1914 to 1918, forced soldiers to endure conditions that can only be described as nightmarish. The trenches, often hastily dug in muddy fields, became cesspools of filth and disease. Infested with rats the size of small cats, soldiers fought an unrelenting battle against nature as much as the enemy. These rats, feeding on decaying corpses littered across no man’s land, spread disease and gnawed on sleeping men. Lice were an equally constant torment, burrowing into the seams of uniforms and causing unbearable itching. Attempts to remove them were futile, as infestations returned within days. Then there was the mud—thick, suffocating, and omnipresent. Soldiers sank knee-deep in this sludge, which swallowed boots and claimed lives when men slipped and drowned in waterlogged trenches. It was a battlefield that offered no respite, where the fight for survival went beyond bullets and shells.

The psychological toll of life in the trenches was devastating, leaving soldiers to grapple with what would later be termed shell shock—the precursor to modern PTSD. The relentless bombardments, often lasting days, turned the trenches into a cauldron of fear and madness. The sound of exploding shells, the sight of comrades torn apart, and the constant anticipation of a gas attack pushed soldiers to the brink of mental collapse. Many experienced trembling, nightmares, and uncontrollable weeping, symptoms dismissed by military leaders as cowardice at the time. The mental scars were lifelong, with survivors returning home unable to reintegrate into normal life. The trenches did not just claim lives; they shattered minds and crushed spirits. Despite their bravery, soldiers became mere pawns in a war of attrition, living in a purgatory that exposed the raw brutality of industrial warfare. Life in the trenches was not just a test of endurance—it was a grim reminder of humanity’s capacity for destruction.

Legacy of World War I: A Shattered Peace and Enduring Memory

The end of World War I in November 1918 marked a new chapter in global history, but its legacy was far from a resolution. The establishment of the League of Nations in 1920, envisioned by President Woodrow Wilson as part of his Fourteen Points, was a bold yet flawed attempt to prevent future conflicts. The League aimed to create a platform for diplomacy, where nations could resolve disputes without resorting to violence. However, its weaknesses were glaring. The absence of key powers like the United States, which refused to ratify the Treaty of Versailles, severely undermined its authority. Furthermore, the League lacked the means to enforce its resolutions, relying on moral persuasion rather than military action. When Japan invaded Manchuria in 1931 and Italy attacked Ethiopia in 1935, the League’s inability to intervene decisively revealed its impotence. Rather than fostering peace, the League became a symbol of international disillusionment, a precursor to the failure of diplomacy that would lead to World War II.

The legacy of World War I is also etched into the landscapes and societies of the countries that bore its brunt, with memorials and remembrance ceremonies serving as poignant reminders of the war’s devastating toll. In France and Belgium, cemeteries like Tyne Cot, the largest Commonwealth War Graves Commission cemetery, house the remains of thousands of soldiers who perished in battles such as Passchendaele and Ypres. These sites, marked by rows of white headstones, stand as solemn tributes to the sacrifices of young men who never returned home. Similarly, the Menin Gate Memorial in Ypres bears the names of over 54,000 soldiers whose bodies were never recovered. In Britain, the tradition of Remembrance Day, held annually on 11 November, honours the fallen with ceremonies, poppies, and moments of silence. Yet, these acts of remembrance are bittersweet; they commemorate bravery while serving as grim reminders of the futility and human cost of war.

Despite these efforts to honour the dead, the peace that followed World War I proved fragile, largely due to the punitive terms of the Treaty of Versailles, signed on 28 June 1919. The treaty imposed harsh reparations on Germany, totalling 132 billion gold marks, crippling its economy and fostering resentment. The territorial losses and the infamous War Guilt Clause (Article 231) humiliated Germany, sowing the seeds for the rise of extremism and the eventual outbreak of World War II. The League of Nations and the memorials stand as stark contrasts—one a failed experiment in diplomacy, the other a haunting reminder of the sacrifices made. Together, they encapsulate the enduring legacy of World War I: a world forever changed, where the pursuit of peace came at the cost of immense human suffering.

FAQs on World War I’s Legacy

Q1: Was the Treaty of Versailles designed to punish Germany unfairly?

Yes, many historians argue that the Treaty of Versailles was excessively punitive. The War Guilt Clause and enormous reparations humiliated Germany, fostering resentment that directly contributed to World War II.

Q2: Did the League of Nations fail due to Western arrogance?

Partially, yes. The absence of powerful nations like the United States and the League’s Eurocentric approach to diplomacy undermined its credibility and ability to resolve global conflicts.

Q3: Were colonial troops deliberately forgotten in World War I’s legacy?

Absolutely. Despite the immense sacrifices made by over 4 million colonial soldiers from Africa, Asia, and the Caribbean, their contributions were largely ignored in post-war commemorations and narratives.

Q4: Did trench warfare prove that military leaders had no regard for human life?

Many argue it did. The Battle of the Somme and Verdun demonstrated a shocking indifference to human suffering, with generals persisting in outdated strategies that caused millions of unnecessary deaths.

Q5: Was Gavrilo Princip a freedom fighter or a terrorist?

This remains highly divisive. To Serbian nationalists, Princip was a hero fighting Austrian oppression, but to others, his actions on 28 June 1914 were reckless, plunging the world into a catastrophic war.

Q6: Did World War I end imperialism, or did it strengthen it?

Ironically, it strengthened it in some ways. The war resulted in the reallocation of colonies under the League of Nations Mandates, reinforcing imperial control under a different guise rather than granting freedom to colonised nations.

Q7: Was the global peace after World War I doomed from the start?

Yes, the peace was precarious. The Treaty of Versailles planted seeds of conflict, and the League of Nations lacked the enforcement mechanisms to address rising tensions, leading to the inevitability of World War II.

Q8: Did the Allies exploit their own soldiers during the war?

Absolutely. Colonial soldiers were often sent to the frontlines with little regard for their lives, and even European soldiers endured horrific trench conditions that exposed the brutal indifference of their leaders.

Q9: Was World War I preventable?

Many argue it was. Mismanagement of the July Crisis of 1914, unchecked militarism, and the entangled alliances among European powers escalated what could have been a regional conflict into a global catastrophe.

Q10: Did World War I truly “end all wars”?

No, despite President Woodrow Wilson’s claim, the unresolved tensions and harsh peace terms laid the groundwork for even greater global conflict in World War II, making it a tragic misnomer.

References:

League of Nations: Purpose, WWI, and Failure”

World War I

“The Treaty of Versailles: Examining a Legacy

“Treaty of Versailles | Definition, Summary, Terms, & Facts”

“League of Nations – World History Encyclopedia”

World War I

YT links

World War 1 (All Parts)

WW1 – Oversimplified (Part 1)

WW1 – Oversimplified (Part 2)

World War 1, Explained in 5 Minutes!

The First World War: The War to End War | WW1 Documentary